In 1916, Albert Einstein theorized that two merging black holes create ripples in the spacetime fabric, similar to how a pebble creates ripples in a pond. These ripples, called gravitational waves, stretch and squeeze spacetime in amounts so minuscule that they were once believed to be too faint to detect.

But a century later, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the US, an L-shaped facility with arms spanning four kilometers each, detected minute discrepancies in how long lasers travel through each arm, signaling the first detection of gravitational waves.

Now, scientists are preparing to launch a more sophisticated observatory into space, aiming to detect even fainter gravitational waves or those beyond LIGO’s capabilities. This space-based facility, known as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna or LISA, is a triangular observatory with sides spanning tens of millions of kilometers and is set to launch in the 2030s.

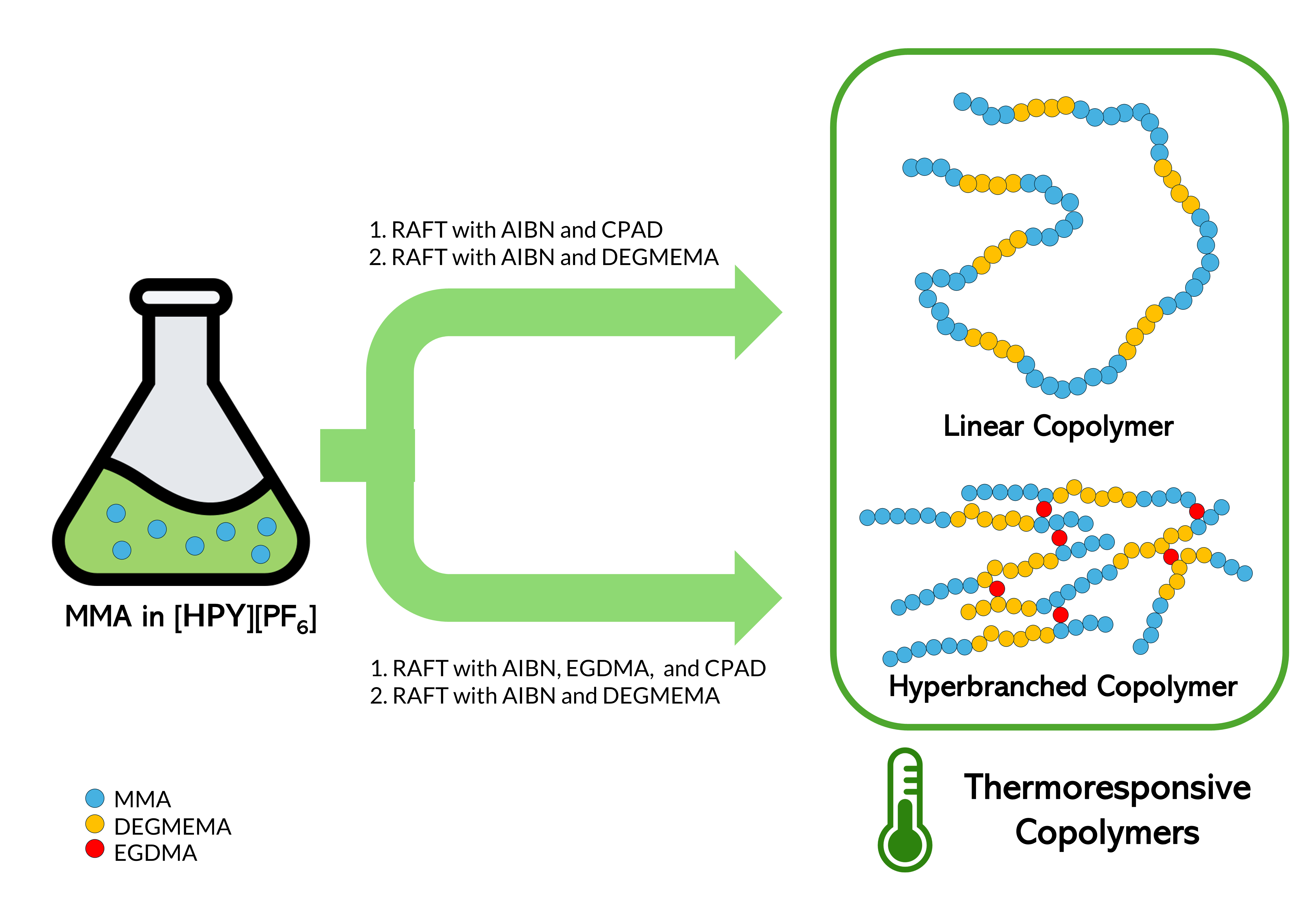

As preparation ramps up, scientists around the world are pitching ideas to improve LISA’s detection capabilities. Dr. Reinabelle Reyes and her former graduate student Marco Immanuel Rivera, from the UP Diliman College of Science’s National Institute of Physics (UPD-CS NIP) recently published a study identifying a set of parameters that could improve the analysis of signals coming from LISA and future gravitational-wave observatories.

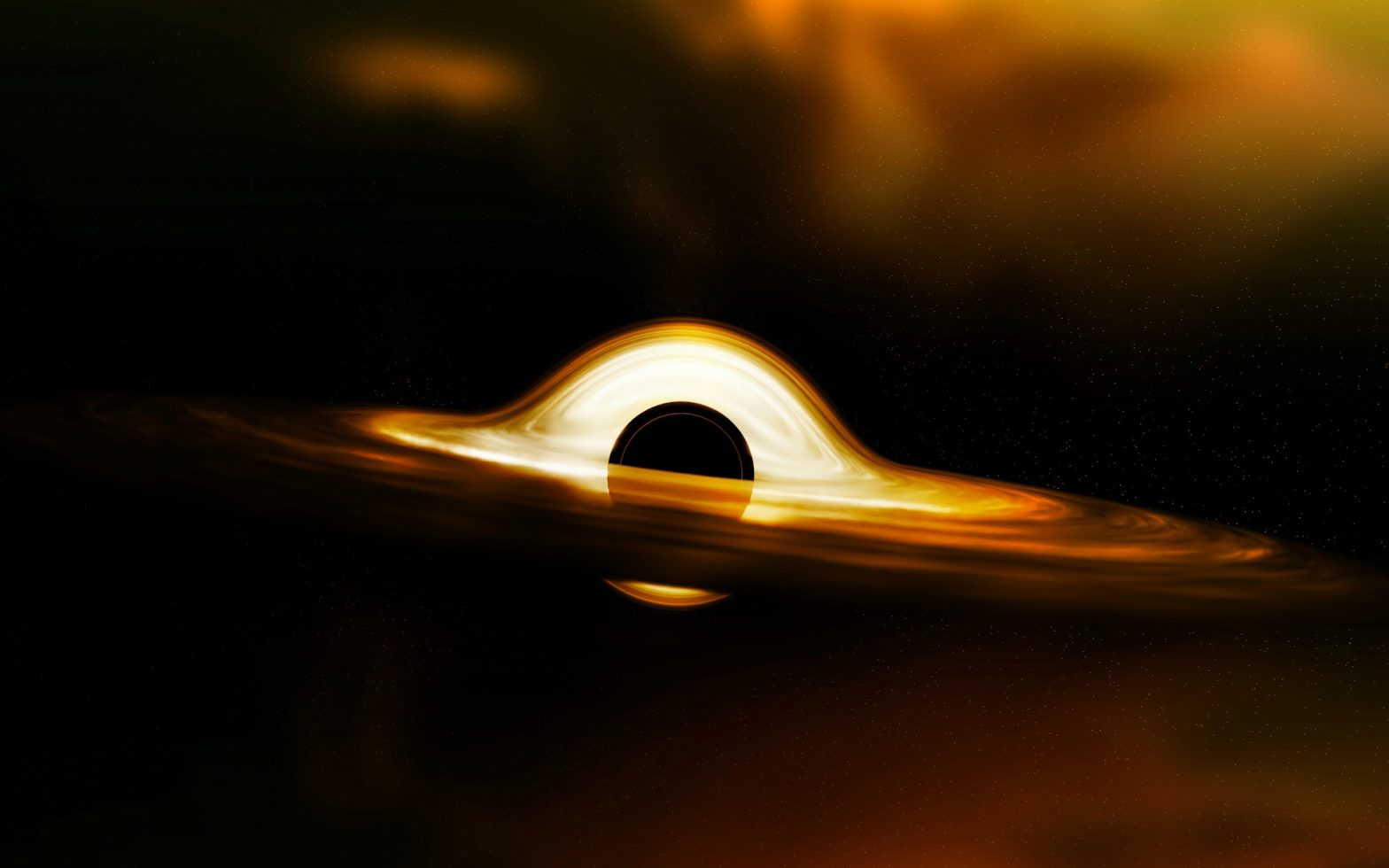

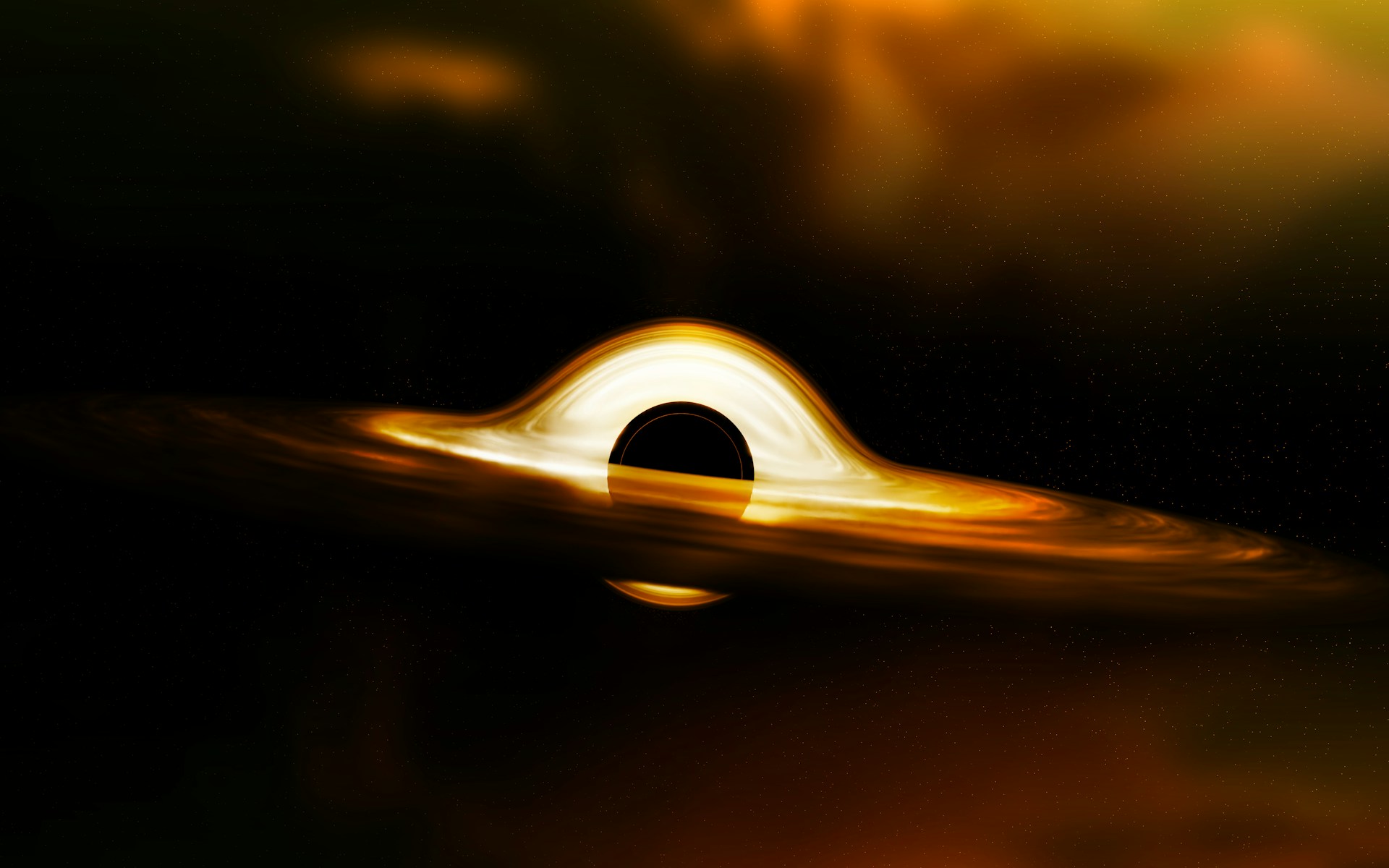

Unlike LIGO, which mainly detects gravitational waves coming from two stellar-mass black holes, LISA hopes to detect a type of gravitational wave coming from compact objects – such as neutron stars, white dwarfs, and stellar-mass black holes – orbiting supermassive black holes. “When a stellar-mass black hole orbiting a supermassive black hole falls into it, an extreme-mass ratio inspiral (EMRI) gravitational-wave signal is produced,” Dr. Reyes and Rivera explained.

One complication with detecting EMRIs is that the environment where the compact object-black hole pair resides can considerably affect the EMRIs they emit. For example, supermassive black holes are often surrounded by glowing rings called accretion disks, which can modify the EMRI signal just as the Earth’s atmosphere distorts light from faraway stars.

By understanding how these environmental features affect EMRIs, astronomers can not only filter out noise from the signal but also learn about the environment itself. For instance, by studying the imprints of the environment on the gravitational wave signal, astronomers can infer the density of the accretion disk.

Their study considered three environmental factors that may substantially influence the EMRI signal: accretion, gravitational drag, and gravitational pull. Their analysis determined the most measurable parameter combination, which is heavily dominated by these environmental effects. They also estimated how precisely these parameters can be measured—an essential factor for extremely sensitive detectors like LISA.

Their analysis is built upon a mathematical tool called the Fisher matrix, which evaluates how accurately an experiment can measure different observables. To illustrate, imagine a catch basin designed to collect water, rocks, and leaves. The Fisher matrix determines and quantifies how effectively the basin can catch each object separately, even before the experiment is set out.

“The Fisher matrix is used by astrophysicists to estimate the expected precision to which certain properties can be measured from a given signal to be observed in a future detector,” explained the authors.

While their study shows promise, Dr. Reyes and Rivera noted that modeling EMRIs is challenging due to strong gravity effects, and more accurate modeling is needed. “It will be interesting to compare with calculations based on the newer waveform models which are adapted for EMRIs, as well as those which contain the effects of non-trivial environments,” the authors said.

“In the future, we hope to see how the parameter combinations we presented in this study can be applied directly in improving parameter estimation methods used in gravitational-wave astronomy, such as stochastic samplers,” the authors concluded.

For interview requests and other concerns, please contact media@science.upd.edu.ph.

Rivera, M.I. and Reyes, R.C. (2024) Measurable parameter combinations of environmentally-dephased EMRI gravitational-wave signals, New Astronomy, 112, p. 102263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newast.2024.102263