The relationship between Super Typhoon occurrence and Climate Change

The relationship between Super Typhoon occurrence and Climate Change

Our country is not new to typhoons and its devastating impacts. Each year, about 20 tropical cyclones traverse the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR). Tropical cyclones occur when the following conditions are present: (1) warm ocean, (2) ample convection (air rising), (3) humid environment, (4) low wind shear, (5) 500 km away from the equator, and (6) a pre-existing low level disturbance. However, even if all these conditions are present, tropical cyclones may not form. Tropical cyclones that form over tropical oceans tend to move west and northward. It is often characterized by strong winds and intense rains that can bring destruction along its path.

Tropical cyclones form when thunderstorms in the monsoon trough (located over tropical waters east of the Philippines) group together and follow a spiral motion. Tropical cyclones can occur anytime of the year in the western Pacific due to the presence of an environment conducive to formation all year round. The Philippines, being located on the western rim of the western Pacific, is vulnerable to tropical cyclones forming in the region.

In the Philippines, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAG-ASA) classifies tropical cyclones depending on their maximum wind strength. These classifications include—from lowest to highest—Tropical Depression, Tropical Storm, Severe Tropical Storm, Typhoon, and Supertyphoon.

Having different thresholds and categories with other countries, PAG-ASA categorizes a supertyphoon when a typhoon’s maximum winds reach >200 kmph. Some of the supertyphoons recorded in the Philippines are Bagyong Rolly in 2020 and Bagyong Lawin in 2016. Despite Yolanda’s wind speed passing as a super typhoon, it was only classified as a typhoon back then. Bagyong Yolanda was also the reason for PAGASA to adopt the term “super typhoon” as a classification.

Known internationally as Typhoon Haiyan, Bagyong Yolanda made its landfall in the country on November 8, 2013 in the Eastern Visayas region. It peaked at ~235 kph, affecting more than 14 million people and causing around 6,300 deaths. Apart from the strong winds, the most destructive was the storm surge that struck the Leyte Gulf. The City of Tacloban in Leyte was the most affected and was declared to be 100% destroyed after the typhoon.

According to the Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology Professor, Dr. Gerry Bagtasa, there is not enough data yet to conclude that climate change is one of the major causes of the increasing number of typhoons and its severity. “Several studies show a relationship between rising ocean temperature and typhoon intensity, however, weather records are rather short at ~40 years starting when satellites were developed. It is therefore difficult to have strong conclusions for now” he explains. In fact, the year 2021 was a strange one because the number of tropical cyclones so far recorded this year is way lower than the previous years.

Although the impact of climate change on tropical cyclones has not been directly observed yet, it is expected that the influence of climate change on tropical cyclones will become clear, and we will likely know this within our lifetime. It is also important that we always prepare for the adverse impacts of typhoons and impose policymakers to implement better disaster-management strategies and shift the focus to preventing damages from happening instead of fixing the damages as a result of typhoon occurrence.

References:

https://www.pagasa.dost.gov.ph/information/about-tropical-cyclone

https://windy.app/textbook/how-typhoons-form.htmlv

https://www.wired.com/story/what-is-a-super-typhoon-and-why-are-they-so-dangerous/

https://www.rappler.com/nation/lookback-super-typhoon-yolanda-haiyan-anniversary-2021

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-probably-increasing-intensity-tropical-cyclones

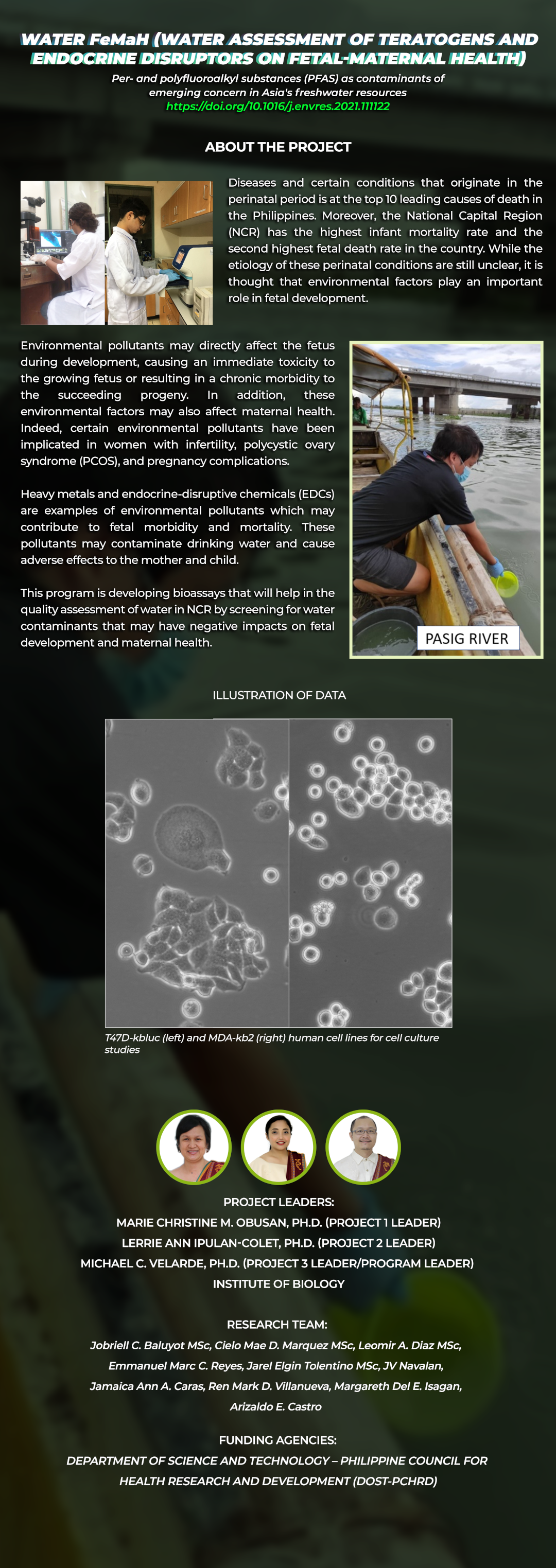

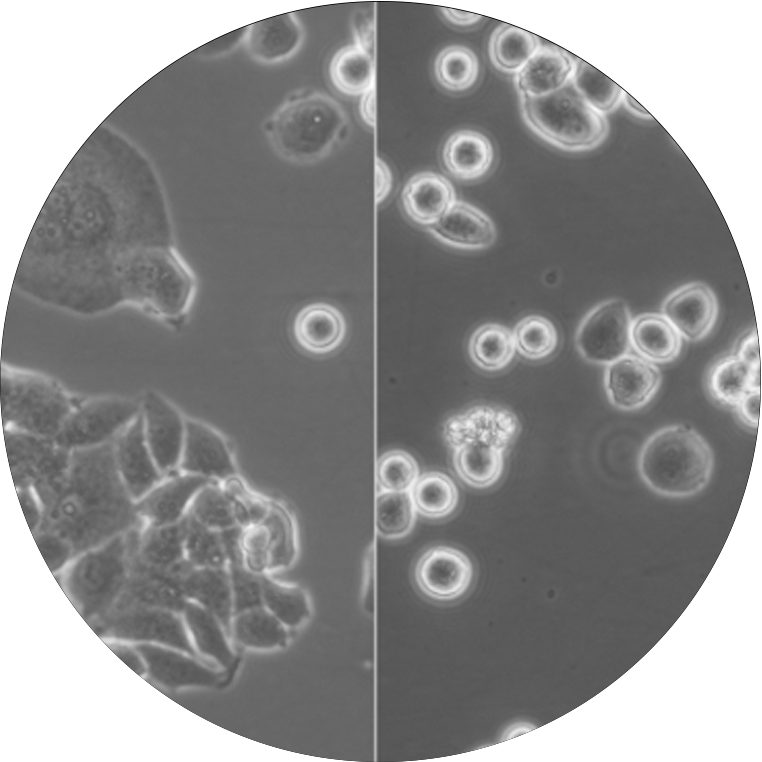

WATER FeMaH (Water Assessment of Teratogens and Endocrine disruptoRs on Fetal-Maternal Health)

Impact of light pollution to local biodiversity

Impact of light pollution to local biodiversity

With the continuous urbanization happening all over the world, environmentalists are concerned about the progressing light pollution that sparks problems on health, biodiversity, safety, astronomy and even in the energy economy.

Light pollution remains as one of the most pervasive forms of environmental alteration and a major global issue. Light pollution is caused by inefficient or unnecessary use of anthropogenic and artificial light in the environment, especially during night time, exacerbated by excessive, misdirected or obtrusive use of light which fundamentally alters natural conditions.

UP Diliman Wildlife and Field Biologist Jelaine Gan further explains the negative impacts of light pollution to the local biodiversity. She says that this creates a novel condition in ecosystems, disrupting the activities of local species thriving in these areas.

Gan states that nocturnal animals are the most affected by this environmental alteration, stating moths as an example. “Insects might get confused and can alter their behaviors which will affect their sleep cycles, reproduction, and the ecosystem,” she says. Another negative effect that may happen is frogs getting disoriented with their body clocks which will prevent them from hunting properly and keeping away from danger.

Nocturnal birds like owls and nightjars may also have a hard time hunting because of their visibility, which also means that they can be easily harmed by humans. Additionally, glaring lights in an area may also affect the foraging of bats and mating behaviors of animals like fireflies.

Light pollution affects the marine environment too. Artificial lights can alter the behavior of marine organisms, species interactions, and food webs and can therefore disrupt marine ecosystems. Sea turtles that are naturally guided by moonlight during migration might get confused and lose their ways which will increase their risk of dying due to predation and hunger.

As a concerned biologist, Gan suggests some known alternatives to reduce light pollution. One is to use smarter structural designs in streetlights and other artificial outdoor lights. They can be angled downwards and intensity can be lowered, enough to serve their purpose. “As a large-scale effort, we can designate areas for night wildlife and astronomical observations like urban parks… a dedicated space for nightscapes,” she adds.

It is undeniable that most environmental pollution are caused by humans and our inventions. That is why it should also be our responsibility to restore the environment’s natural state. It is important that policy makers continue to develop and uphold laws that control pollution and administer the creation of alternative technologies that not only save energy but also reduce light pollution.

References:

https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/light-pollution/

https://www.darksky.org/light-pollution/wildlife/

https://www.manilatimes.net/2021/04/10/opinion/columnists/after-noise-pollution-what-next/862125

https://meam.openchannels.org/news/skimmer-marine-ecosystems-and-management/artificial-light-may-be-changing-marine-ecosystems

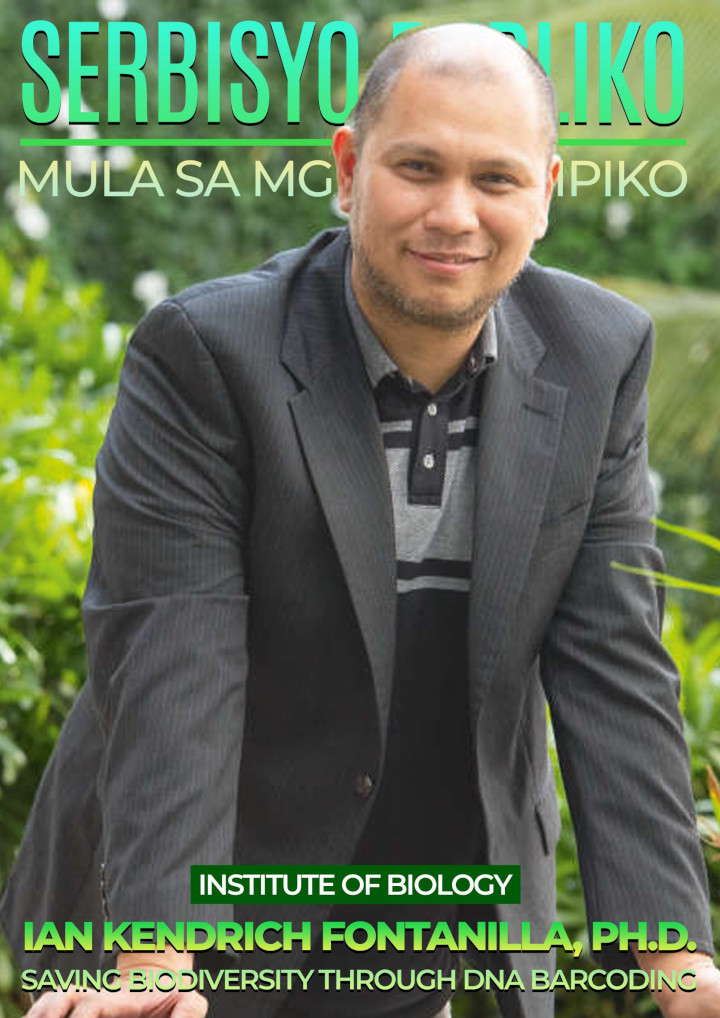

Dr. Ian Kendrich Fontanilla – Institute of Biology

Dr. Ian Kendrich Fontanilla - Institute of Biology

In 2013, a Chinese vessel with over 3,000 frozen pangolins onboard was caught in the Tubbataha Natural Park in Sulu Sea. The pangolins were already processed and their scales were removed, making it hard to identify if they belonged to the endemic Philippine species, Manis culionensis, and if the Chinese fishermen should be prosecuted under the Republic Act No. 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act. The authorities seeked help from experts to identify where the pangolins came from to determine their next course of action. A team from the UP Diliman Institute of Biology (IB) headed by Dr. Ian Kendrich C. Fontanilla came to rescue and with the samples provided, they concluded that the pangolins were only closely related Southeast Asian species.

In 2013, a Chinese vessel with over 3,000 frozen pangolins onboard was caught in the Tubbataha Natural Park in Sulu Sea. The pangolins were already processed and their scales were removed, making it hard to identify if they belonged to the endemic Philippine species, Manis culionensis, and if the Chinese fishermen should be prosecuted under the Republic Act No. 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act. The authorities seeked help from experts to identify where the pangolins came from to determine their next course of action. A team from the UP Diliman Institute of Biology (IB) headed by Dr. Ian Kendrich C. Fontanilla came to rescue and with the samples provided, they concluded that the pangolins were only closely related Southeast Asian species.

The case was different in 2016 when their team found out that the 73 pangolin specimens confiscated from illegal traders in Puerto Princesa were indeed Philippine pangolins. In a more recent case, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) brought to the same team some samples of cured meats or “tapa” that were claimed to be from deer and wild pigs and were being sold in the market. This is considered illegal under the RA 9147. Upon their analysis, the meat was found to be just from a domesticated pig.

These cases of illegal wildlife trafficking, misrepresentation and scamming were confirmed, proved and supported by the DNA Barcoding Laboratory (DBL) in IB, which is currently headed by Dr. Fontanilla. In the laboratory, their team generates DNA barcodes for Philippine endemic species to represent them in the growing PH flora and fauna database. DNA barcoding uses a specific gene from an organism’s DNA to easily identify its species designation. Samples are compared to the current contents of the PH database to find out their closest match. This system can be utilized by wildlife law enforcement officers in the rapid identification of traffic specimens, therefore protecting wildlife from exploitation.

The DBL and Dr. Fontanilla have received praises and distinction for their DNA barcoding work, which they started to build up in 2008. “Through this method, we describe the Philippine biodiversity to know what is out there and what we have,” then 46-year-old UP Scientist says.

The DBL and Dr. Fontanilla have received praises and distinction for their DNA barcoding work, which they started to build up in 2008. “Through this method, we describe the Philippine biodiversity to know what is out there and what we have,” then 46-year-old UP Scientist says.

The DBL has partnered with different government agencies and NGOs including the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Philippine Eagle Foundation, and Energy Development Corporation in their DNA barcoding efforts. These partners provide the endemic species samples that they “barcode” and input in the publicly available database.

Dr. Fontanilla’s lab also works with other laboratories from the UP System such as in UP Baguio and UP Los Banos that apply their DNA barcoding method. These laboratories focus on their own specific taxa. He hopes to continue growing the Philippine database of flora and fauna and to achieve this by collaborating with more partners across the country.

As a professor, one of Dr. Fontanilla’s goals is to mentor new doctoral students that would become the Philippines’ new wave of scientists. “We need to encourage more people to enter the field of research because we need it more than ever.” He also expressed his ideals in spreading UP scientists in different institutes as administrators and policy makers to ensure the effective applications of science to society and to easily share their research to those who need it most.

As a professor, one of Dr. Fontanilla’s goals is to mentor new doctoral students that would become the Philippines’ new wave of scientists. “We need to encourage more people to enter the field of research because we need it more than ever.” He also expressed his ideals in spreading UP scientists in different institutes as administrators and policy makers to ensure the effective applications of science to society and to easily share their research to those who need it most.

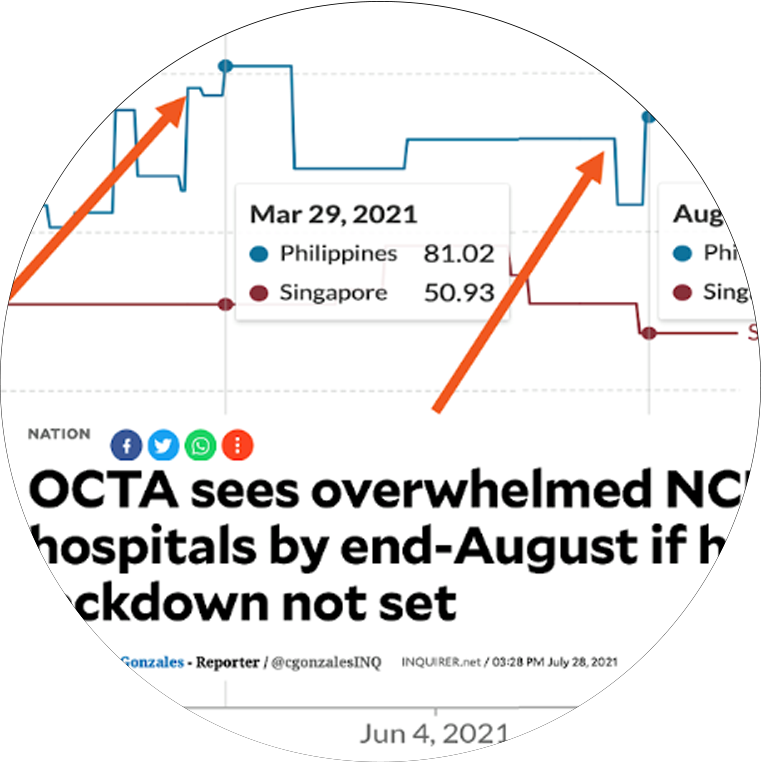

Science advice and policy in a crisis situation: COVID-19 in the Philippines

Bacterial partners and host defenses define the fate of marine sponges in the future ocean

Dr. Reynaldo “Rey” L. Garcia – National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology (NIMBB)

Dr. Reynaldo “Rey” L. Garcia - National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology (NIMBB)

When the pandemic hit and lockdowns were implemented in March 2020, Dr. Reynaldo “Rey” L. Garcia of the National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology (NIMBB) unexpectedly found a bigger and more important role for his laboratory. He volunteered to loan out his laboratory’s RT-qPCR machine and other equipment to COVID-19 testing laboratories and to the Lung Center of the Philippines while they wait for the procurement of these equipment. Together with his research assistants, they also mapped out the locations and created a database of qPCR machines across the country and made arrangements for the loaning and lending to accredited testing labs.

When the pandemic hit and lockdowns were implemented in March 2020, Dr. Reynaldo “Rey” L. Garcia of the National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology (NIMBB) unexpectedly found a bigger and more important role for his laboratory. He volunteered to loan out his laboratory’s RT-qPCR machine and other equipment to COVID-19 testing laboratories and to the Lung Center of the Philippines while they wait for the procurement of these equipment. Together with his research assistants, they also mapped out the locations and created a database of qPCR machines across the country and made arrangements for the loaning and lending to accredited testing labs.

With the help of social media, Dr. Garcia initiated a call for volunteers with RT-qPCR experience who will be deployed to accredited testing centers. Many of the volunteers were his research assistants (RAs) and students who were trained in his laboratory and at the NIMBB. Their call for volunteers was expanded to include medical technologists who could help with swabbing, sample preparation and even RT-qPCR. Some of his RAs also co-founded Scientists Unite Against COVID-19—an alliance of concerned scientists, organizations and other citizens—and launched a massive social media information campaign about COVID-19, COVID-19 testing, and preventing viral transmission.

Because his students and RAs could not volunteer indefinitely, they had to make sure that the country was ready to fight COVID-19 without them in the frontlines. For this, they provided technical training and customized seminars to med techs who will take over their roles. Dr. Garcia’s RAs who were deployed to the Lung Center of the Philippines and the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) spent their last two weeks volunteering by training newly hired med techs who will run the testing labs after they leave.

Dr. Garcia has founded and headed the Disease Molecular Biology and Epigenetics Laboratory (DMBEL) in NIMBB since its establishment in 2011. They focus on the functional characterization of novel non-hotspot mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors, as well as the regulatory roles of non-coding RNAs in cancer pathogenesis. Ten years after its establishment, Dr. Garcia and his lab now maintains an exemplary reputation as one of the most well-equipped laboratories in the country comparable to labs in first world countries.

Dr. Garcia, who has been focusing on cancer research since 1999 in the United Kingdom, has published mainly on colorectal cancer, and most recently on microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs and circular RNAs. Despite a long and fruitful stint abroad, Dr. Garcia decided to come back to the Philippines, bringing with him 20 years of education, training and experience in molecular biology and biomedical research.

He carried on with this passion when he came back to teach and do his research in NIMBB. One of his goals is to study ethnic nuances in the mutational landscape of Filipino cancer patients through his research and this ambition led him to set up DMBEL.

With state-of-the-art laboratory equipment, generous grants from UP and DOST, and highly skilled laboratory personnel, Dr. Garcia and his colleagues have not only reaped interesting and significant research findings, but were also able to respond to emergencies and extend a helping hand during the country’s most critical months.

Apart from DMBEL being able to publish in high-impact international journals, Dr. Garcia also envisions it to be an excellent research laboratory that will produce the next generation of molecular biologists who will help form the critical mass we so badly need. Dr. Garcia hopes that studies done in his laboratory can help improve clinical practice, especially in the area of differential cancer diagnosis and personalized medicine. At the same time, he hopes to produce scientists who are technically capable and globally competitive.

Apart from DMBEL being able to publish in high-impact international journals, Dr. Garcia also envisions it to be an excellent research laboratory that will produce the next generation of molecular biologists who will help form the critical mass we so badly need. Dr. Garcia hopes that studies done in his laboratory can help improve clinical practice, especially in the area of differential cancer diagnosis and personalized medicine. At the same time, he hopes to produce scientists who are technically capable and globally competitive.

For the head of the multi-awarded laboratory, UP and other research and teaching institutes should strive to establish a world class reputation so that they could entice young aspirants to do their PhD and postdoctoral studies locally. “We need to attract highly-driven post-doctoral fellows who are at the peak of their careers,” he says.

Dr. Garcia says he is proud that his lab has come a long way but it also has a lot more to offer. He is constantly working with researchers all over the country in the area of drug discovery and hopes to leverage biodiversity in the Philippines in the search for first-in-class and novel drug candidates.

Dr. Garcia says he is proud that his lab has come a long way but it also has a lot more to offer. He is constantly working with researchers all over the country in the area of drug discovery and hopes to leverage biodiversity in the Philippines in the search for first-in-class and novel drug candidates.

A mathematical model of the dynamics of lymphatic filariasis in Caraga Region, the Philippines

Modeling the transmission of COVID-19 in the Philippines: Case study in selected highly urbanized cities and Optimal age-specific intervention strategies against COVID-19